When we started The Orbital Index, Ben was working at an early-stage VC, and Andrew had just taken his first job in aerospace, building smallsat ground control software at a tiny startup called Kubos. The newsletter was a way for us to learn a new industry, a product design exercise, and a shared experiment in science communication and concise curation by two very long-time friends.

Since then, Orbital Index has developed its own voice and an avid following. Sarajane joined as our incredible assistant editor, and we somehow managed to publish nearly every week for almost seven years.

During those seven years, Andrew journeyed from industry outsider to a founding role at Vast and, later, to co-founding space solar energy startup Overview Energy. Ben used the newsletter as a vehicle to explore space deeply and develop the discipline of writing concisely and clearly—making mission concepts and rocket engine specs understandable without losing technical depth, all while writing significantly more than any of his English teachers ever thought he should.

The space industry has changed a lot during Orbital Index’s tenure. When we started, New Space was, well, new. The first privately funded lunar lander, SpaceIL’s Beresheet, had just launched; Opportunity’s mission had just ended, with Perseverance on the horizon; SpaceX’s Crew Dragon had yet to carry people into space; Starhopper hadn’t hopped and only two Starlink prototypes had flown; the Chinese Space Station hadn’t launched, nor had any of China’s ambitious sample return missions; and, not one commercial Chinese rocket had reached orbit.

Fast forward, and the landscape is dramatically different today. Commercial companies are exuberantly undertaking almost every aspect of space that used to be purely governmental. These ambitions will soon be bolstered by the arrival of significantly lower-cost launch on reusable launch vehicles from across the US, China, and, eventually, Europe.

The next decade of space is going to be incredible, and we’re excited to be involved in our own ways, but the amount of time and attention required to do it justice in a newsletter has grown beyond what we can muster alongside families, careers, and commitments. We both find ourselves at moments of transition, more burdened than energized by the weekly task of writing, and feeling ready for change, with our attention on new horizons and adventures. And so, as bittersweet as it is, this is our 350th and final issue of The Orbital Index.

In this last omnibus issue, we’ll share our incomplete view of where we see the space industry heading in the next decade. ✧✧✧ Private everything. It’s been clear for a while that, step by step, space is joining the domain of private enterprise. Corporations dominate launch, telecommunications, and much of Earth observation. Companies are now actively working on replacing governmental efforts with commercial offerings in space situational awareness, comms (including deep space), cislunar transport (more below), positioning and navigation, and some remaining niches of Earth observation (fire monitoring, CO2 monitoring, and more… but some EO may remain a poor fit for commercial ‘science-as-a-service’ business models). At least in the West, the next space stations will be commercial, as will transport to them. To be clear, this is only possible because of government support for the ISS over the last 30 years and additional funding through NASA’s CLD program. Similarly, NASA’s CLPS contracts have set the stage for increasingly commercial lunar missions. Beyond cislunar space and in the astrophysics and astronomy domains, most missions under development remain national, but that too is slowly changing. Rocket Lab and MIT's Venus Life Finder mission, and a new crop of asteroid mining startups, are slowly pushing the commercial sphere outward. Meanwhile, private non-profit efforts are quietly working on space telescopes, both big ones and somewhat smaller, cheap and mass-produced ones designed to revolutionize the questions that space science can ask. Enabled by the prospect of dramatically lower launch costs courtesy of Starship and New Glenn, private companies are also working on efforts that have no operational governmental analogues, including power beaming, orbital data centers, orbital refueling, in-space manufacturing, and orbital assembly. Like it or not, capitalism seems to be actively heading toward new capital markets the stars. |

|

| | Rocket Lab and MIT’s Venus Life Finder mission, approaching Venus sometime in 2027 or later, to probably not find life. |

|

We hope the Moon likes rovers… cause it’s getting a lot. As lunar exploration ramps up worldwide, our celestial companion is slated to be explored by increasingly advanced rovers over the next 10 years. ⚙️ - Small but mighty: Building on its first successful CLPS Moon landing, Firefly’s next three CLPS landers this decade will all carry rovers: UAE’s Rashid 2 on the second lander, Honeybee Robotics’ first rover on the third—exploring a unique lunar volcano—and on the fourth mission, both Astrobotic’s versatile CubeRover and Canada’s first rover. NASA has also awarded future contracts for Astrobotic CubeRovers to demonstrate power transmission and lunar night survival. This year, Intuitive Machines’ third Moon landing attempt will carry NASA’s Lunar Vertex instruments on the lander along with a rover to study a magnetic swirl, helping us understand the Moon’s evolution. This lander will also deploy NASA’s three CADRE rovers, which collectively will autonomously map the surface and subsurface around Reiner Gamma. ispace US’s first CLPS mission through Draper in 2027 will carry a demonstration rover from the company’s European arm. China’s Chang’e 8 lander will deploy Pakistan’s first rover and two small mobile bots from private Chinese company STAR.VISION. Future Artemis IV astronauts will also deploy a rover, built by Lunar Outpost, which will study lunar dust and surface plasma. And finally, Australia’s first rover, called Roo-ver, will launch by 2030 on an as-yet-unidentified CLPS lander to explore water ice at the south pole.

- Sophisticated: Launching this year, China’s Chang’e 7 rover and hopper, carrying a comprehensive instrument suite, will map and characterize water ice and other volatiles on the Moon’s south pole, crucial for planning sustained crewed and robotic missions. Later this decade, a Chang’e 8 rover and dextrous mobile robot will comprehensively study the south polar geology & environment while also building lunar soil-based structures. Astrobotic’s Griffin CLPS lander will deploy Astrolab’s semi-autonomous FLIP rover on the Moon’s south pole later this year; it got manifested last year after NASA decided not to fly the critical VIPER rover for studying water ice. NASA has now tentatively chosen Blue Origin’s second Mark I lander to hopefully fly VIPER in 2027. The joint ISRO-JAXA Chandrayaan 5/LUPEX rover mission later this decade will drill and analyze south polar water ice, and can provide NASA with critical data that is currently missing in Artemis planning.

- Crew support: China is progressing with prototypes of a small crewed rover as part of its ambitious plan to land humans on the Moon by 2030. NASA, meanwhile, plans to have a cutting-edge Lunar Terrain Vehicle being used by Artemis astronauts across missions starting at the end of this decade. JAXA will provide NASA with an even more advanced rover next decade, which will be pressurized, enabling astronauts to spend weeks exploring in it. In return, NASA has agreed to land two Japanese astronauts on the Moon.

— Contributed by our friend Jatan Mehta. For an expanded rundown of these rovers, read Moon Monday #256. |

|

| | An illustration of Japan’s upcoming pressurized crewed rover for NASA Artemis. A large solar panel covers the other side. Credit: JAXA/Toyota |

|

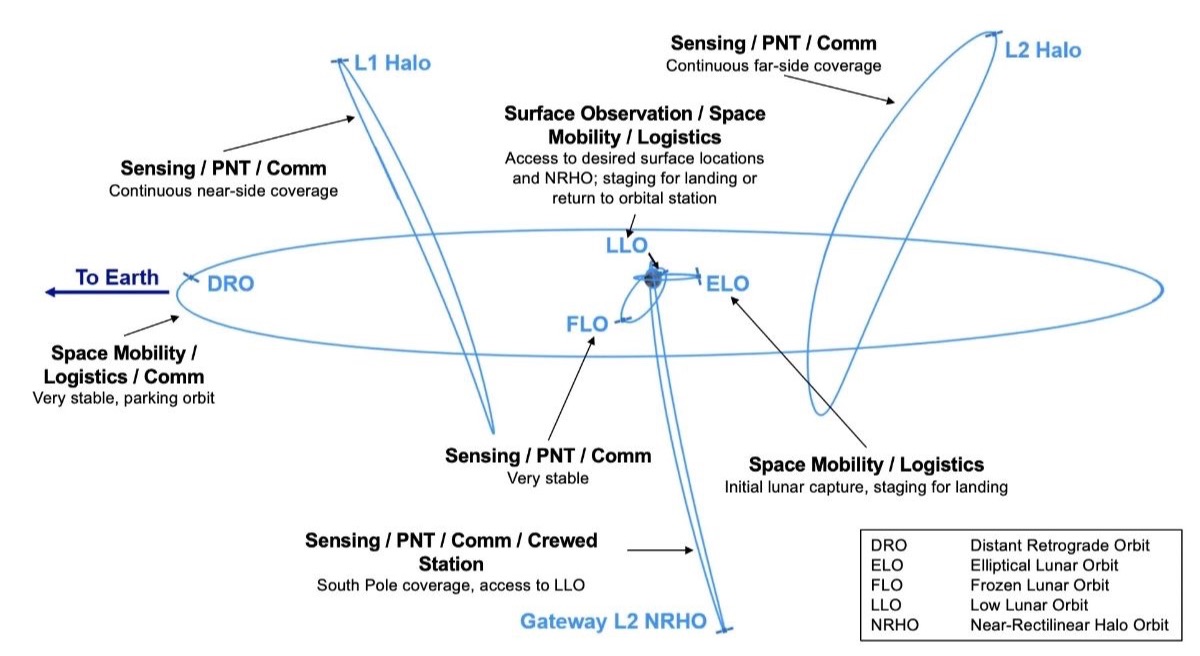

Future of Cislunar Transport. Cislunar space—a 550,000 km-radius spherical region governed by the combined gravitational influence of the Earth and Moon, including the five Earth–Moon Lagrange points—is poised to see a sharp increase in activity as lunar ambitions shift from short-duration visits to sustained presence. Driven largely by U.S. and Chinese programs, more than 100 missions are already planned for the Earth–Moon system over the next decade, spanning science, infrastructure, communications, and national security. This growing cadence is pushing cislunar space to host a transportation network rather than merely being a destination, shaped by its relatively low energy cost to access and the operational demands of heavier Earth–Moon traffic. From a delta-v standpoint, injecting payloads onto cislunar transfer trajectories (~3.2–3.9 km/s from LEO) is comparable to reaching geosynchronous orbit (~4.1–4.3 km/s), but once there, spacecraft must operate reliably within the dynamics of the three-body system, contend with a weak and irregular lunar gravity field, and actively maintain unstable orbits such as near-rectilinear halo orbits (Gateway will be in an L2 NRHO if it actually launches). These conditions make cislunar space an ideal environment for maturing in-space transport capabilities, forcing a transition from single-use missions toward sustained mobility. Future architectures increasingly rely on reusable transfer vehicles, space tugs, and logistics platforms capable of repeated rendezvous, continuous station-keeping, and multi-year operations—capabilities already implicit in the logistics requirements of NASA’s Artemis program and Lunar Gateway, as well as China’s Chang’e-derived lunar infrastructure roadmap. NASA recently funded initial studies into low cost commercial platforms such as Blue Origin’s Blue Ring and Impulse’s Helios kickstage toward a model in which cislunar transport functions as a service, moving spacecraft between Earth orbit, lunar orbit, and interplanetary departure points. These systems demand reusable propulsion, long-duration operation, and flexible mission profiles. In contrast, DARPA’s (surprising) decision to cancel the DRACO program (c.f. Issue № 229) highlights the near-term prioritization of chemically- and electrically-propelled architectures over higher-risk nuclear thermal propulsion. In the emerging cislunar architecture, the central technical challenge is no longer reaching cislunar space, but operating reliable, repeatable transportation systems within it—establishing the logistical backbone required for sustained lunar operations and eventual missions to Mars and beyond. — Contributed by Sarajane Crawford, our amazing assistant editor for the past 3 years. |

|

| | A diagram showcasing the varying orbits and subsequent use cases available in cislunar space, highlighting the need for flexible transport options. |

|

So many more rockets. In the seven years we’ve been writing Orbital Index, the commercial launch sector has seen the first few vehicles reach space from companies founded this century. But the NewLaunch world, imagined as a bustling marketplace featuring a plethora of launch providers vying for market share, driving costs lower, and consistently launching, has largely failed to materialize. Falcon 9 and Electron remain the only new, non-governmental vehicles with truly mature flight heritage, and they have only recently been joined by New Glenn, Firefly Alpha (with its recent mixed record), Vulcan, and Zhuque-3, all with single-digit successful launches. However, waiting in the wings is a growing cadre of will-definitely-launch-in-the-next-two-years rockets, which have almost become too numerous to track (ed. actually, it’d be great if someone built a web app to track all of them—but until then, there is a lovely list of all the small launchers). Here’s a partial list in rough order of our best guess of the likelihood of the next vehicles to successfully reach orbit sometime kinda-sorta-soonish: Starship (wenorbit?), Neutron (recent fairing test), Stoke Space Nova, Relativity Terran R (recent update video), Gilmour Eris Block 1, Hanbit-Nano, Isar Spectrum, Space One Kairos, RFA One, Orienspace Gravity-2, Northrop/Firefly Eclipse, Interstellar Zero, Skyrora XL, Space Pioneer Tianlong-3, Galactic Energy Pallas-1, Orbex Prime, PLD Space Miura 5, MaiaSpace Maia, i-Space Hyperbola-3, Skyroot Vikram-1, Deep Blue Nebula-1, and Astra Rocket 4. Several of these could be ranked higher, but don’t have publicly manifested non-governmental customers, meaning they’ll be slower to become truly ‘commercial.’ Our opinion is that reusability will, unsurprisingly, be the biggest determining factor in the business success of these rockets once they make it to orbit, mitigated in the near-term by vehicles with strong government contracting success.

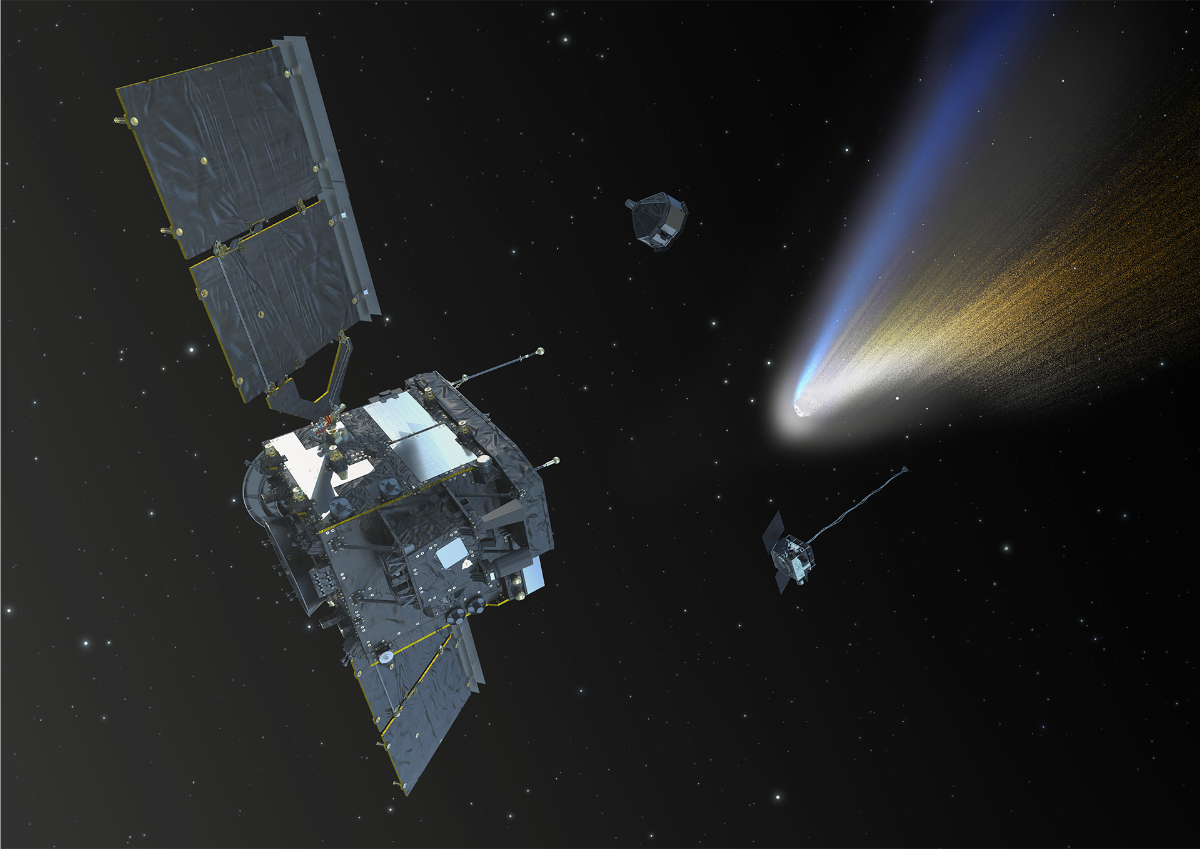

Space science. Over time, the availability of low-cost launch will rewrite the manual for space science, just like everything else in orbit. Lower costs enable iteration and scaled production, allowing mission designers to take more risk and adapt standardized interfaces to their own science questions (a la Cosmic Frontier Labs, linked above). These platforms will replace some of the exquisite, failure-is-not-an-option missions of today, along with their astronomical price tags. Blockbuster missions, though, will still have a place, and many are in the works, even despite the current US Administration’s dislike of science and active threat to ~41 space missions—some late-breaking good news here, though. NASA is still officially pursuing Dragonfly, the Roman Space Telescope, and several others, although much remains uncertain. Meanwhile, the rest of the world has been and will continue to be stepping up, especially ESA (we’re excited for Comet Interceptor, PLATO, ARIEL, EnVision, eventually LISA, and a load of important Earth science missions) and China (missions to the Moon, Mars, asteroids, and later Jupiter, and maybe Uranus and Neptune). There are also ambitious Korean, Japanese (MMX!), Indian, and Emirati missions. As mentioned above, we also expect more private deep-space and science missions over time. It’s clear that science isn’t going to wait around for NASA, and we’re also quietly optimistic that, under the new leadership of Jared Isaacman, NASA will be back in the game sooner than many of us feared. 🤞 🔭 |

|

| | ESA and JAXA’s Comet Interceptor approaching an unknown future comet (or interstellar object?) after having loitered in space waiting for its unsuspecting prey and a moment in the sun. |

|

Space and Earth: the decade ahead. The next decade is vanishingly small on the timescale of planets, but it is likely to be a critical one for humanity, with space playing its own crucial role. And while the current US administration is pushing to cut Earth Science programs, personnel, and missions (both in development and operational; c.f. recent NCAR shutdown news), that doesn’t change the fact that modern climate science emerged in part from the truly global vantage point provided by our ability to put people, cameras, and sensors in orbit. While budgets are under fire at NASA/NOAA/USGS/etc, much of the rest of the world seems to understand that this work remains existential. ESA has more Earth Science missions in development and operation than ever before (we’re particularly excited for FORUM, Copernicus CO2M, and FLEX), JAXA is staying the course on its own small set of missions (ISS-hosted MOLI and PMM), China is beginning to add its version of Earth Science missions (TanSat-2 and DQ-2), and multiple smaller nations have missions in progress (Canada’s WildFireSat, Norway’s AOS-P, and South Korea’s recently launched KOMPSAT-7). These missions and the data they’ll produce are critical, as humanity is blowing past its +1.5 ºC warming limit after a decade of record average global temperatures and mounting climate-induced disasters. These realities firmly place us in uncharted territory; we don’t know how quickly or how drastically climate patterns will shift as a result, particularly given our limited understanding of climate tipping points that will likely accelerate warming (if you like board games, Daybreak is fun and our favorite that includes tipping points). Our ability to mitigate atmospheric methane and its sources (leaks, flaring, etc.); understand cloud behavior at particle, single-cloud, and weather system scale; measure carbon cycle components like biomass; and, monitor resilience metrics like surface temperature, moisture levels, and wildfires will only grow in importance as humanity comes face-to-face with its most daunting self-inflicted problem to date (AI may very well be next). As we’ve shared before (c.f. Issue № 48), here at Orbital Index we’re unabashedly in support of treating climate change as the massive problem and opportunity that it is and of focusing humanity’s substantial ability to produce, problem-solve, and build on securing a livable and pleasant future—one where we can turn our focus toward the stars without ignoring existential threats at home. ✧✧✧ We know many of you will miss The Orbital Index (and we’ll miss you too!). As we wind things down, we plan to move the current mailing list to a new list dubbed Orbital Index: Extended Mission. We might use it occasionally for space-related thought pieces or updates if the inspiration strikes, but we’re making no promises, and there definitely won’t be a regular cadence. In the meantime, don’t hesitate to send us a note.

Please also follow us individually: Ben (LinkedIn, Twitter/X, BlueSky), Andrew (LinkedIn, Twitter/X, BlueSky) & Sarajane (LinkedIn, BlueSky)

Fortunately, if you feel the need to plug an Orbital Index-sized hole in your inbox, there are other excellent space newsletters out there. Here are some we recommend: ✧✧✧ Thank you to all of our supporting members who made this newsletter possible: Evan Maynard, Will Deaton, Marijan Smetko, Sam Anderson, Thomas Smyth, Thomas Paine, Manuel Imboden, Galen Stevens, Samuel Trask, Bill Allen, David Rolling, Eliot Gillum, Dave Gallagher, Jesse Coffey, Lindy Elkins-Tanton, William Aaron, Brian, Frederic Jacobs, Michael Barton, John Frank, Austin Link, Ben Frank, Mike Curtis-Rouse, Matt Harbaugh, and Dan Gluesenkamp. (To those of you who opted to keep your support anonymous, thank you too!)

We also couldn’t have done it without generous corporate sponsors, listed here in order of first appearance: Spaced Ventures, Xometry, Back to Space, Formlogic, Epsilon3 (our longest sponsor at 211 issues, right up to the end; thank you!), First Resonance, Spire, A.I. Solutions, Elodin, AllSpice.io, and CSC Leasing.

Thanks for sticking with us to the very end. And so, for now… so long and thanks for all the fish!

—Andrew & Ben

✧✧✧ |

|

| Humanity’s last view of JWST, departing to stare deep into the cosmos. |  |

|

|