¶Mishaps and mission endings. This year has seen a number of missions suffer failures or unexpected mishaps of varying severity. These failures serve as a reminder that space continues to be a complex, high-stakes endeavor and that objectives like lunar landings (5 governments and 1 commercial lander have ever done this), orbital human space launch (3 countries ever), and rocket reuse (1 rocket, 1 orbital space plane upper-stage) are all massive undertakings. - B1062, SpaceX’s life-leading Falcon 9 booster, launched for its 23rd successful time last week, delivering 21 Starlink satellites to orbit. However, on landing, one of its four landing legs failed, causing the booster to topple over, destroying the venerable rocket. The FAA briefly grounded Falcon 9 for a second time in the same number of months, but since there was no public danger, the agency allowed F9 to return to flight almost immediately, clearing Polaris Dawn for launch on B1083 as soon as later this week. This was the first failed landing in over 3 years—as SpaceX pushes the limits of reuse, we expect to see more landing failures, and 23 launches on a rocket is a pretty good run.

- Peregrine-1’s maiden voyage in January had its chances of success destroyed just after launch by a faulty valve, which allowed high-pressure helium into the craft’s oxygen tank, rupturing it. The lunar lander was guided to responsibly re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere 10 days later. (Valves are notorious points of failure on space systems, including early Falcon 9 landing failures.)

- JAXA officially ended the mission of SLIM, the country’s first Moon lander, last week. Originally only expected to operate for a single lunar day and then feared to be doomed after it landed in the incorrect orientation after losing an engine bell, the mission managed to survive 3 lunar nights and complete all pre-mission success criteria. SLIM is the first lunar lander to successfully perform a “pinpoint” landing, arriving within 10 meters of its selected landing site.

- In July, ABL Space lost its RS-1 flight article during a static fire test at its pad in Kodiak, Alaska. The test was aborted due to a low-pressure reading from a faulty sensor. After the abort, fuel leaks from multiple engines fed a pad fire that was controlled by gaseous and water fire suppression systems until the water supply ran out after 10 minutes. The fire then grew, eventually leading to the booster crumpling onto the pad at T+23 minutes. ABL believes the leaks were caused by an unexpectedly high-energy startup of the new Block 2 booster, leading to combustion instability. Last week, the company reduced its headcount (Ed., tbh, one of the best layoff letters we’ve ever read, but that’s not really an award anyone wants to get) but still hopes to make it to orbit and has its next booster well into production.

- Optimus, Australia’s largest commercially and domestically built small sat, launched for ~$1.7M on Transporter-10 this spring. However, Space Machines, the startup behind the 280 kg satellite, struggled to identify the satellite immediately after the launch. After several weeks, engineers managed to identify the craft but could never establish ground comms with it. This is an ongoing trend, with satellites failing because they can’t passively survive due to expectations of precise pointing (aka “point or die”), requirements of specific thermal management scenarios, batteries that can’t last for hours or weeks before ground contract is established (e.g. lacking sufficient trickle charging side mount PV panels), or communications that are not omnidirectional and easy to initiate.

- On August 19, Rocket Factory Augsburg lost their first RFA ONE flight article in a static fire test, reminiscent of ABL’s loss just a month earlier. According to RFA (video), the root cause of the loss was a fire in one engine’s oxygen turbopump, leading to damage to a propellant manifold. Protective measures in place were not sized to withstand an oxygen-rich scenario, causing most of the engine components and nearby equipment to be consumed by the fire. RFA ONE’s second and third stages and fairing were unharmed and will await integration at SaxaVord with the company’s next first-stage flight article (containing 100+ improvements, many of which are to the propellant and pressurization systems).

|

|

| RFA ONE mid-collapse as its oxygen-rich fire rages out of control. (Watch the video.) |

|

The Orbital Index is made possible through generous sponsorship by:

|

|

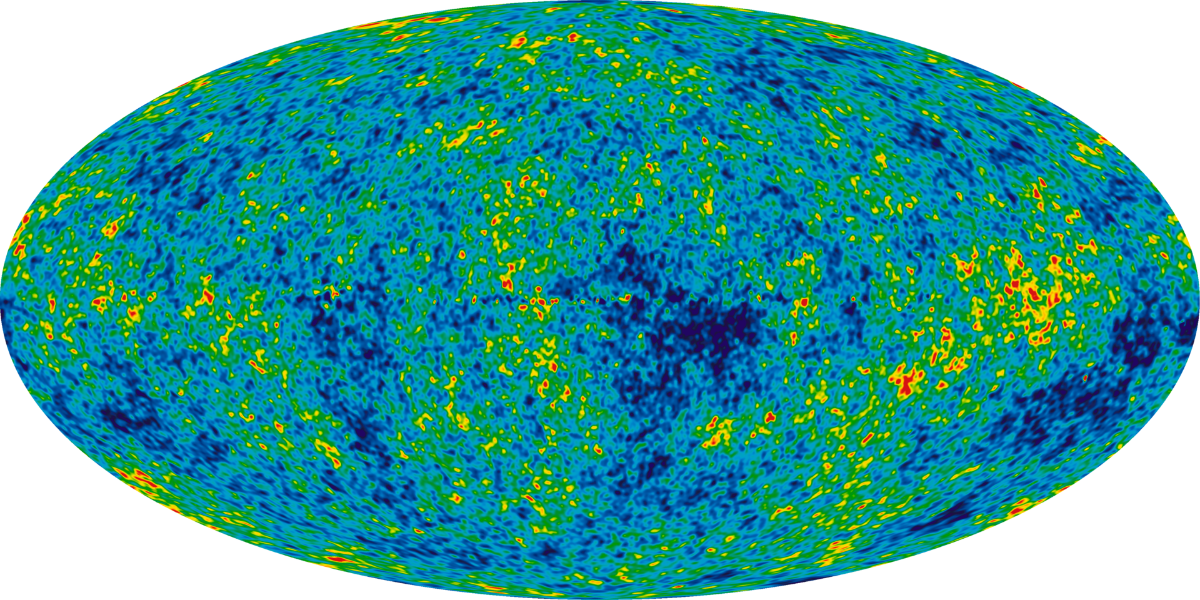

¶Inflation. Not the monetary kind, but rather cosmic inflation. We used to describe the Big Bang as the beginning of the Universe, but we now consider the Big Bang to be a moment some unknown amount of time after a period of exponential inflation. During inflation, space was doubling in size every tiny fraction of a second, expanding quantum fluctuations in energy density to enormous scales even as new fluctuations were formed. Eventually, and randomly, regions of space would stop inflating, converting the inflationary field into a hot, dense soup of matter and radiation that we consider the hot Big Bang. The theory of inflation attempts to explain why the observable Universe is so uniform, but also its slight, almost scale-invariant non-uniformities—due to quantum fluctuations blown up to intergalactic size by inflation—and why it’s so flat. These quantum fluctuations’ signatures are seen in the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) and the large scale structure of the Universe. Evidence for gravitational waves created by inflation will also hopefully show up in future detections of CMB polarization. More broadly, the random end to inflation itself isn’t may not have been uniform, such that each “region where a Big Bang occurs will be surrounded by more inflating, exponentially expanding space, ensuring that no two regions where hot Big Bangs occur ever collide, intersect, or overlap.” (If inflation continues eternally, and if these regions of nucleated non-inflating space were each left with different physical constants, it would help explain the seemingly tuned nature of our Universe while we would only find ourselves in a region with constants compatible with our own existence—but while aesthetically appealing, this conjecture is seemingly untestable. (Related to this problem, Stephen Hawking’s last cosmology paper attempted to solve for inflation without requiring that it be eternal.) |

|

| The cosmic microwave background temperature fluctuations (± 200 microKelvin) as recorded by the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe over 9 years. |

|

¶Regional space activities: South America 🌎. Though South America’s roots in space technology and development date back to the 1950s, getting off the ground has remained challenging for the continent due to economic and political reasons. There are ~75 South American owned-and-operated satellites in orbit (as of late 2023) and nearly 85 observatories. Only two astronauts of South American birth have made it to space (Peruvian Carlos Noriega and Brazilian Marcos Pontes), but among the 12 sovereign states, none have built an orbital launcher (yet). Seven states have national space agencies (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, Peru, and Venezuela), with three others having space programs (Uruguay, Ecuador, and Colombia), and six (Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, Peru, Ecuador, and Venezuela) involved in the formation of the 21-country Latin American and Caribbean Space Agency (ALCE), which began development in 2020 with a budget of $100M—ALCE’s objectives include advancing the role of LatAm women in space and launching a first geostationary satellite for the region. Brazil’s space program, started in 1961, is the most developed within the region but has faced several hurdles. During the construction of Brazil’s Alcântara Launch Center in the 1980s, Quilombola communities were forcibly expelled and are still seeking adjudication from the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. Activity at the Alcântara Launch Center was reduced following a 2003 explosion that resulted in the loss of 21 lives and the destruction of the domestic VLS-rocket program’s launch tower. Some of Brazil’s indigenous people are afraid that more displacement will occur given the proposed expansion of the launch center by 12,000 hectares. Brazil has overseen 500+ launches from Alcântara over 40+ years (including three recent suborbital launches between 2021-23), developed the domestically-built Amazônia-1 satellite, and is working to develop the VLM-1 orbital rocket capable of launching 150 kg by 2026. The CNES-owned Guiana Space Center (CSG) in French Guiana has hosted 300+ launches, most of them Vega and Ariane 4 & 5 orbital launches—the facility’s next-generation flagship launcher, Ariane 6, just lifted off in July. Russian space agency Roscosmos launched the European variant of its Soyuz-2 rockets from CSG for 10 years until the 2022 announcement that it was ceasing operations following Russia's invasion of Ukraine. CSG operations were interrupted in 2017 by protesting labor unions and indigenous peoples—CSG resumed operations after a relief package of up to €2.1 billion was pledged. Isar Aerospace has been chosen to become the first commercial tenant at CSG, while bids are underway to take over the old Soyuz launch site (MaiaSpace, RFA, and Avio are all potential tenants). Meanwhile, Argentina is making progress on the two-stage Tronador II rocket—its RS-2 engine thrust chamber was recently manufactured. The country also has domestic satellite capabilities, and has multiple space centers to support experimental launches, satellite operations, and future Tronador launches. |

|

| The VLS launch tower at Alcântara Launch Center after the VLS-1 V03 accident on 22 August 2003, which killed 21 people. The disaster occurred when a solid rocket motor on the VLS-1 ignited unexpectedly days ahead of its launch. |

|

‹Support Us› Orbital Index is made possible by readers like you. If you appreciate our writing, please support us with a monthly membership! |

|

| ¶News in brief. NASA’s Advanced Composite Solar Sail System spacecraft unfurled its 80 square meter solar sail and is preparing for testing ● Blue Origin launched their eighth crewed New Shepard mission, carrying six people (including a NASA-funded scientist) to suborbital space ● NASA awarded Intuitive Machines a $116.9M contract to deliver six payloads to the Moon’s South Pole, marking the 10th CLPS cargo contract (with the south pole location, 2027 timing, and ~80 kg of payload well within a range that could pair well with an IM-funded VIPER delivery…) ● Impulse Space received $60M in SpaceWERX government funding to develop a third stage for medium-lift rockets that aims to carry payloads to high Earth orbits in less than a day (as opposed to months-long orbit raising from LEO) ● Europa Clipper will likely still launch in October after NASA analyzed radiation-risky transistors (c.f. Issue 278) and concluded that they could support the baseline mission ● Loft Orbital and Marlan Space launched Orbitworks, a joint venture with a $100M initial investment that aims to produce satellites up to 500 kg in Abu Dhabi ● Stoke Space won a $4.5M Defense Innovation Unit contract to prototype a point-to-point cargo delivery system ● Galactic Energy launched their third Ceres-1 solid rocket from a mobile sea platform ● Axiom Space is partnering with Nokia to develop 4G/LTE communications for their lunar spacesuits ● A car-sized meteorite fell (harmlessly) over a populated area near Cape Town, South Africa. |

|

¶Etc.- There are some excellent free courses online for learning astrophysics and cosmology. Some of our favorites include From the Big Bang to Dark Energy taught by Hitoshi Murayama from The University of Tokyo, Astrophysics: Cosmology taught by astrophysicists Brian Schmidt and Paul Francis from the Australian National University, and especially the really excellent The Science of the Solar System by Mike Brown of Caltech. Mike Brown is famous for his hunt for Planet 9 and for helping to make Pluto no longer a planet. Jerk.

- If you actively work in the space industry, you’re invited to join Space Network, a Slack group of space industry professionals that we’ve loved for a while now.

- We mentioned microlensing last week, so here is a detailed article about microlensing and the hunt for rogue planets. Many rogue planets are exoplanets kicked out of their home stellar systems by encounters with other planets or passing stars, but some seem to have instead formed through direct collapse (like how stars form)—540 of these may have been found in the Orion Nebula last year (paper), and JWST recently spotted six more. Along with China’s Earth 2.0 (cf. last week’s issue), the Roman Space Telescope will be searching for these wandering planets in the void in years to come.

- An in-depth look at DRACO and the coming return of nuclear thermal rockets.

- “Rise and Stall of GPS”: A Payload article exploring the aging GPS constellation, highlighting that over half of GPS satellites have outlasted their designed lifespans, with the oldest remaining operational for an impressive, yet somewhat unsettling, 27 years.

- “NASA is gonna need $2.7 billion for another SLS rocket. Oh, wait, sorry, just for the thing to move and hold the rocket.” NASA’s second mobile launcher for SLS is probably about $2.3B over budget, on an originally $400M project. (The world’s largest building, the Burj Khalifa, is seven times taller and cost about half the estimated total.)

- Fitting an elephant with four non-zero parameters… or one. 🐘

|

|

Remnants of SpaceX’s Falcon 9 booster B1062 that caught fire and tipped over after landing on the A Shortfall of Gravitas droneship. Credit: John Kraus |  |

|

|