¶Papers- ESO’s VLT observed a rogue planet—a free-floating planet unbound to any star—rapidly accreting material (paper). This observation suggests that some rogue planets may form through accretion, like stars, rather than forming in a stellar system and then escaping.

- Observations in 2023 show rings of debris forming around the small, 200 km solar system body Chiron, which orbits between Saturn and Uranus. If accurate, this would be the first time we’ve watched rings form (paper).

- Pulsars typically stop pulsing under a certain rate of rotation. However, some pulsars have been observed to be active even below this expected limit. The culprit might be tiny mountains, just centimeters tall, which would amplify local electric fields and enable lower-energy emissions (paper). The researchers also propose that for this to be true, neutron stars might be made of "strangeon matter," an “exotic form of matter bound together by the strong nuclear force rather than electromagnetic forces. This material would be tough enough to maintain surface features against the neutron star's extreme environment, with binding energies millions of times stronger than ordinary matter.”

- A pair of white dwarfs, 150 light-years away, are slowly spiraling toward each other (with energy radiated as gravitational waves). The duo has a combined mass of 1.56 Suns, making them the heaviest Type Ia supernova progenitor system identified, well over the 1.4 solar-mass Chandrasekhar limit (paper). When they eventually make contact and go supernova, they’ll be ten times brighter than the full Moon when viewed from Earth. On the other hand, it’s unlikely Earth will exist in ~23 billion years when this happens.

- A black hole 10 billion light-years away probably consumed a massive star in a tidal disruption event and emitted a flare 30x brighter than any previously observed from a black hole (paper). At its peak, it shone with the light of 10 trillion suns. Sounds a bit poetic, don’t it?

|

|

| “We haven't actually seen a star fall in since we invented telescopes, but I have a list of ones I'm really hoping are next.” XKCD #3072 |

|

The Orbital Index is made possible through generous sponsorship by:

|

|

¶High-flying filling stations, off-planet petrol, & the future of fuel. Since the beginning of the Space Age, orbital refueling has remained an unfulfilled dream that promises to revolutionize the space industry—primarily by extending the life and range of spacecraft. Refueling would enable greater mass dedicated to payload at launch, more complex in-space assembly, access to new and more plentiful target destinations, and more reusable space tugs. Liquid methane (LCH4) boils at -162 °C, oxygen (LOx) at -183 °C, and hydrogen (LH) at -253 °C, while other common liquids freeze in space, including RP-1 (-51 °C), hydrogen peroxide (−0.89 °C), water (0 °C), and hydrazine (2 °C). Storing these propellants in space, therefore, requires advanced thermal management to prevent boil-off or freezing using tank geometry, materials and insulation, active cryocoolers/heaters, sun shades, and other thermal control systems. Challenges also include microgravity effects on propellant (difficult liquid mass gauging and unpredictable liquid/gas distribution), increased operational complexity due to rendezvous, proximity operations, and docking (RPOD) for transfers, propellant depot orbital accessibility, hydrogen embrittlement of storage tanks, and the need to periodically refill depots. But technology is slowly inching toward refueling. Starting in March 2007, DARPA’s Orbital Express mission performed multiple hydrazine fuel transfers between the prototype servicing satellite (ASTRO) and a surrogate satellite (NextSat), and NASA’s Robotic Refueling Mission (RRM) included three phases of cryogenic fuel transfer work on the ISS in the 2010s. Orbit Fab’s Tanker-001 Tenzing launched to a sun-synchronous orbit (SSO) in 2021, carrying high-test hydrogen peroxide (HTP) to test the Rapidly Attachable Fluid Transfer Interface (RAFTI) fueling port. SpaceX’s Starship Flight 3 in March 2024 tested refueling technologies by transferring 5+ metric tons of cryogenic LOx from one internal tank to another. Earlier this year, the Chinese Shijian-25 demonstration refueling satellite docked with Shijian-21 and potentially transferred propellant. Upcoming missions include NASA’s LOXSAT (NET early 2026), which will demo a cryogenic fluid management system. Orbit Fab plans to deliver up to 1,000 kg of xenon gas to power the ion thrusters of Astroscale’s Life-Extension In-Orbit (LEXI) geostationary servicing satellite (NET 2026), and up to 50 kg of hydrazine to one of the two Tetra-5 satellites operated by the U.S. Space Force (both via an integrated RAFTI port). Astroscale’s Prototype Servicer for Refueling (APS-R) will attempt to refuel the other Tetra-5 satellite in mid-2026, while Northrop Grumman’s Passive Refueling Module (PRM) will refuel Tetra-6 in 2027. Of course, the ultimate goal—one that would drastically reduce launch cost on Earth—would be to have all stages of propellant production (mining, processing, and storage) performed in space to avoid hauling liquids out of Earth’s deep gravity well |

|

| A 1971 concept of an orbital propellant depot. Credit: NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center. |

|

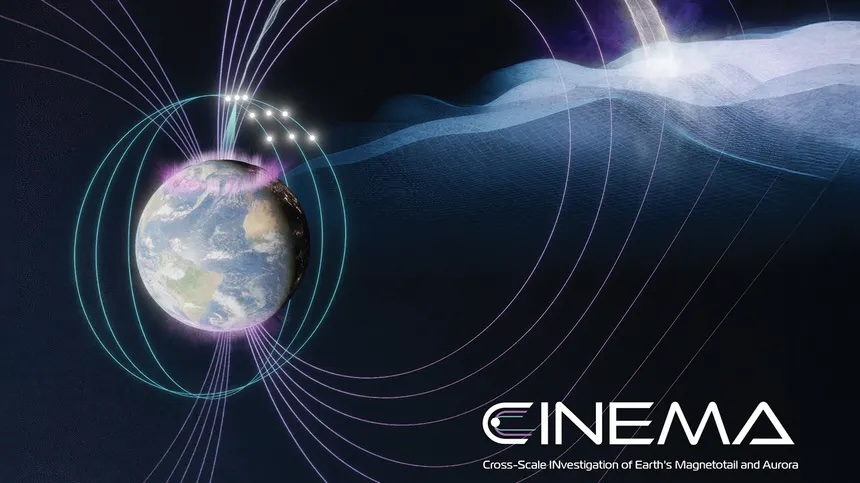

¶CINEMA and CMEx move forward. Cross-scale Investigation of Earth’s Magnetotail and Aurora (CINEMA) is a small-class explorer mission focused on improving our understanding of magnetic convection in Earth’s magnetotail, which drives energetic, sometimes explosive, plasma flows associated with aurorae and fast plasma jets. The mission will now move into Phase B development, planning the flight system and mission operations. If selected for full development, with a total mission cost not to exceed $182.8M (excluding launch), CINEMA would launch nine formation-flying small satellites into three planes in polar orbit, each carrying an identical instrument set including an energetic particle detector, an auroral imager, and a magnetometer. Meanwhile, CMEx (Chromospheric Magnetism Explorer) was selected for an extended Phase A study (12 months; $2M). CMEx is a proposed single-spacecraft concept that builds on proven UV spectropolarimetric instrumentation demonstrated on NASA’s CLASP sounding rocket flights, and would observe the Sun’s inner chromosphere to understand the origins of solar eruptions and identify the magnetic sources of the solar wind, supporting improved space-weather prediction relevant to satellite and astronaut safety. |

|

| If fully developed, Cinema’s nine cubesats will fly on three orbital planes, creating a grid of identical sensors to measure Earth’s magnetotail. |

|

‹Support Us› Orbital Index is made possible by readers like you. If you appreciate our writing, please support us with a monthly membership! |

|

| ¶News in brief. All eight docking ports on the ISS were occupied simultaneously for the very first time—spacecraft included both cargo and crew variants of Dragon, two Soyuz and two Progress vehicles, Japan’s HTV-X1, and a Cygnus XL ● NASA lost contact with MAVEN, a spacecraft that's been circling Mars since 2014 ● Two Chinese taikonauts conducted a spacewalk to inspect the damaged window on the Shenzhou-20 and install additional debris protection on Tiangong ● China and Brazil began building a joint space astronomical laboratory, despite US pressure in Latin America to minimize ties to China ● AnySignal raised a $24M Series A to ramp up their radio manufacturing operations ● K2 Space raised a massive $250M Series C to continue building high-power satellite buses ● SpaceX reused a Falcon 9 booster for the 32nd time, a new record—Falcon 9 has now more than 3x’d its original reuse goal of 10 flights ● British startup Odin Space raised a $3M seed round to develop sensors that allow spacecraft to detect sub-centimeter orbital debris ● California-based Fortastra raised $8M in seed investment to develop orbital defense satellites ● NASA astronaut Jonny Kim and two Russian cosmonauts returned to Earth aboard a Soyuz M-27 after an eight-month stint on the ISS. |

|

| Russia’s Soyuz MS-27 capsule landing in a remote area near Zhezkazgan, Kazakhstan, bringing one NASA astronaut and two Russian cosmonauts back to Earth after an eight-month stint at the ISS |

|

¶Etc.- This Proton M rocket explosion from 2013 (slow motion HD video) is WAY too much like the rockets Andrew used to build in KSP. Related: things KSP teaches you that are wrong.

- Do datacenters in space make economic sense? A long-form, delightfully interactive, deep dive from Andrew McCalip.

- If you made a beach out of sand grains proportionate in size and quantity to the stars in the Milky Way, what would that beach look like?

- A look at Skylab’s final orbit and reentry in 1979, including a pieced-together audio track of the final telemetry and NASA commentary during tracking.

- The Space Freighter and Star-Raker single-stage-to-orbit space plane, envisioned in the 1970s for delivering massive components to space for space solar energy and other missions.

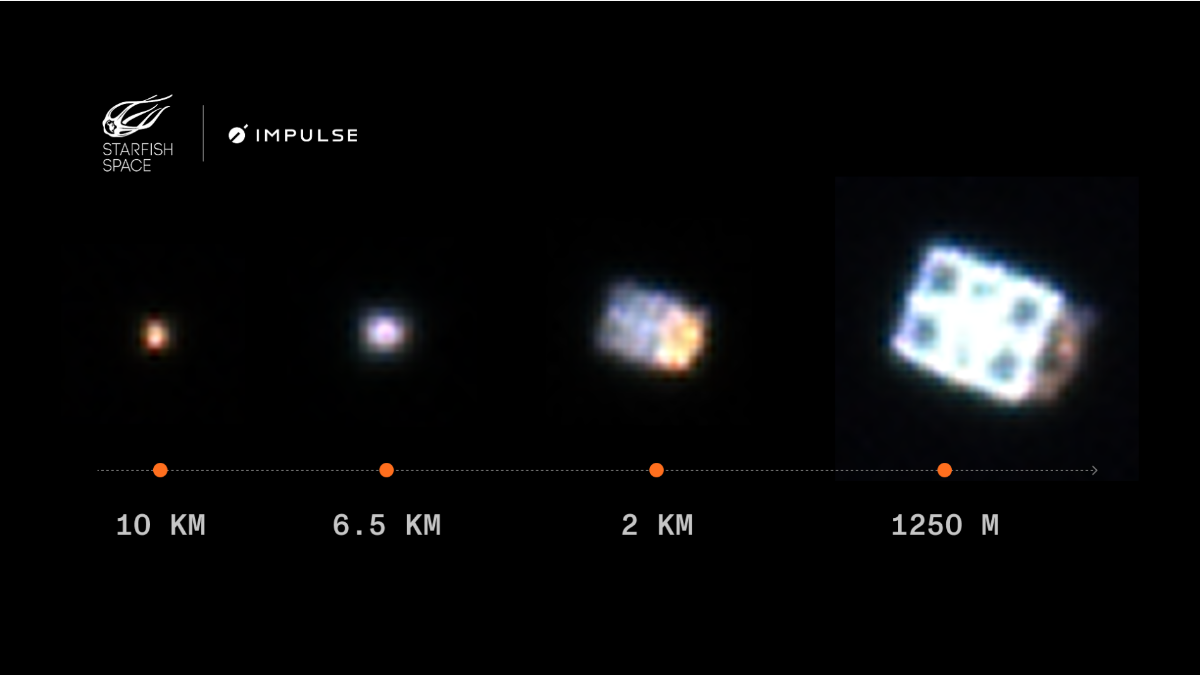

- Impulse and Starfish quietly conducted an RPO(D) experiment over the past several months (minus the D), using Starfish’s software and Impulse’s Mira spacecraft to bring it within 1,250 km of an older Mira vehicle. The Impulse vehicle, using high-thrust chemical propellants, was not heavily modified to enable this mission, other than the addition of a single camera and Starfish’s flight computer. The mission was named Remora after the fish that attaches to a host.

|

|

Mira as seen from (a newer) Mira. Starfish took pictures during the approach of the unsuspecting older sibling to Impulse’s latest space tug. |  |

|

|